Free Will Part 1: Quantum Mechanics

Quantum Mechanics, Determinism, & Occam’s Razor

The free will debate is this obnoxious debate that no matter how many years goes by always stays in its infancy.

That’s not how things are supposed to be.

Years later, your theories should have more nuance, more distinction. They should have - if not more complexity, more description.

But determinism never gets more descriptive. It never gets more nuanced. And it never feels like a complex explanation to explain what is a very complex topic within human nature.

I often look at determinism as a sort of stunted debate, in the sense that it doesn’t lead to productive discussion. In fact, it closes down productive discussion. It rarely explains itself. And it rarely explains the phenomenon of our experiences.

I’m not a fan of an exploration of human nature that shuts down all discussion of human nature.

Thus, my dissatisfaction with the arguments set forth in the debate makes me abstain from participating as often as possible.

But not because I don’t have my own views on free will. In fact, I have enough views on the “parameters of free will” to write a whole book. As an Existentialist, I believe that freedom and choices are the components that make up human nature and our societies.

And so, privately, I’ve spent many years crafting my own subjective nuance surrounding some aspects of the debate.

I’d like to share some of them here. This isn’t an exhaustive explanation, but it’s some beginning points:

This series of articles will be divided into three main articles:

Part 1: Quantum Mechanics, Material Determinism, & Occam’s Razor

Part 2: Being Alive, Sentient Movement, Religious Determinism, & Entropy

Part 3: Intelligence & Willpower Via Causal Relationships

Part 1: Newtonian Mechanics vs Quantum Mechanics

I’d like to start with what appears to be the main premise of deterministic will.

The idea that because we exist in a causal universe, that somehow The Big Bang was a single movement that set off a chain of events that makes everything else exist.

And thus, we’re a product of a long chain of causal events that led up to the moment we decided to pick up a spoon and eat oatmeal for breakfast. And nothing was ever free or freely chosen in this deterministic lineage of a universe.

(If your determinism has a more descriptive version, please post below).

I’m not sure what to say to this description. Except that it’s based on Newtonian Mechanics and not on Quantum Mechanics.

Gregory J. Chaitin

So I’m going to post my responses via two other thinkers. One is the mathematician Gregory J. Chaitin who says in his book, Conversations With A Mathematician:

“In theory, in Newtonian physics or classical physics, you can predict the future. The equations are deterministic, not probabilistic. If you know the initial conditions exactly, with infinite precision, you can apply the equations and predict with infinite precision any future time––and even the past, because the equations work either way, in either direction.

In Newtonian physics, you can calculate the precise trajectory of a particle and know exactly how it’s going to behave. But in quantum mechanics, the fundamental equation is an equation dealing with probabilities.

The idea in quantum mechanics is that randomness is fundamental, it’s a basic part of the universe … You can’t know exactly where an electron is and what its velocity vector is.

It doesn’t have a specific state that’s known with infinite precision the way it is in classical physics.

If you know very accurately where an electron is, then its velocity or momentum turns out to be wildly uncertain. And if you know exactly in which direction and at what speed it’s going, then its position becomes infinitely uncertain. That’s the infamous Heisenberg uncertainty principle.”

Carlo Rovelli

Carlo Rovelli is an Italian theoretical physicist. In his book Reality Is Not What It Seems, he gives a slightly more technical description than Chaitin. He writes:

“Werner Heisenberg .. emerges, sometime later, with a disconcerting theory: a fundamental description of the movement of particles, in which they are not described by their position at every moment, but only by their position at a particular instant––the instant in which they interact with something else.

This is a second cornerstone of quantum mechanics, its hardest key: the relational aspect of things. Electrons don’t always exist. They exist when they interact. They materialize in a place when they collide with something else. The “quantum leaps” from one orbit to another consitute their way of being real: an electron is a combination of leaps from one interaction to another. When nothing disturbs it, an electron does not exist in any place.”

Rovelli goes on to write:

“Paul Dirac’s quantum mechanics is the mathematical theory used today by any engineer, chemist, or molecular biologist.

The theory gives information on which value of the spectrum will manifest itself in the next interaction, but only in the form of probabilities. We do not know with certainty where the electron will appear, but we can compute the probability that it will appear here or there.

This is a radical change from Newton’s theory, where it is possible, in principle, to predict the future with certainty. Quantum mechanics brings probability to the heart of the evolution of things.

This indeterminacy is the third cornerstone of quantum mechanics: the discovery that chance operates at the atomic level.

While Newton’s physics allows for the prediction of the future with exactitude - if we have sufficient information about the initial data, and if we can make the calculations - quantum mechanics allows us to calculate only the probability of an event. This absence of determinism at small scale is intrinsic to nature.

An electron is not obliged by nature to move toward the right or the left––it does so by chance.

The apparent determinism of the macroscopic world is due only to the fact that the microscopic randomness cancels out on average, leaving only fluctuations too minute for us to perceive in everdafe.

Chaitin goes on to show a really easy way of looking at this: astronomers use Newtonian physics to calculate where the planets will be seen in the sky every night.

But a casino thrives on randomness, for example, with a roulette wheel, because if there was a pre-determined effect, you would be able to learn it and use it to win.

So how did we get here?

If quantum mechanics is the prevailing theory of physicists today and it shows that an atom isn’t deterministic, but is instead, able to move at random toward the left or the right––then how can a human being’s behaviors be MORE deterministic than an atom?

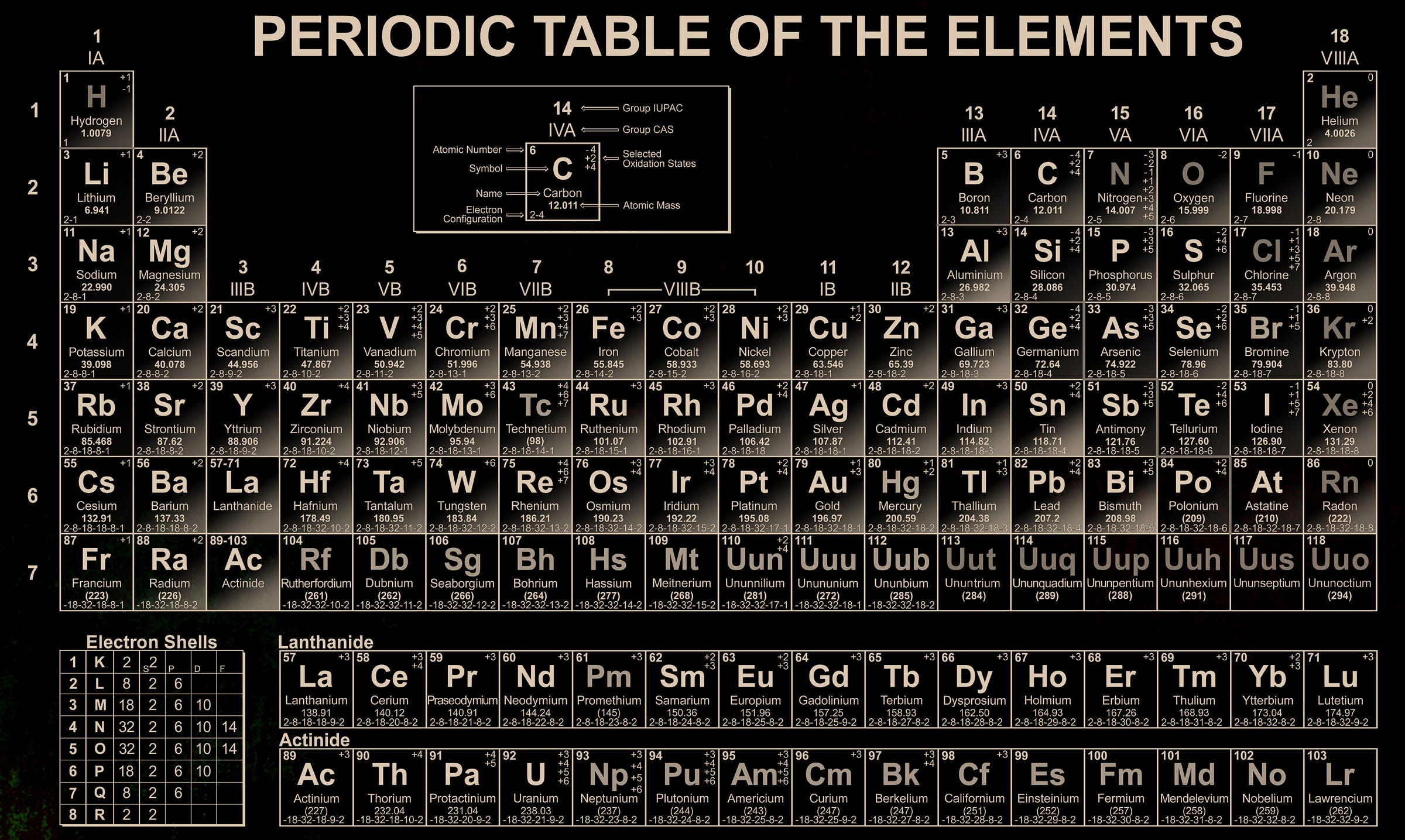

Especially given that human beings are much more erratic and subjective than the behaviors of any element on the periodic table.

Playing Out The Nature Of Causal Relationships

Let me explain how I see cause and effect playing out in a deterministic universe. It won’t be the perfect description, but at least this how I make sense of it.

When two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom come together, water is reliably formed. We deduced this by trying to understand the pre-determined causal relationship between one thing and another.

And even though quantum reality exists, all of the behaviors of the elements on the periodic table are still commonly spoken of as causal. Because the elements are still fairly predictable.

Perhaps the best way to say it, is that the probability is finite. The causes have finite effects. And so we can reliably predict their behavior.

We think of causal relationships as a pre-determined link between two things, in which something does not have the choice to say “no, I don’t want to.” And instead, the same thing happens over and over again.

When two hydrogen atoms meet an oxygen atom, the oxygen doesn’t get to say “I don’t feel like becoming water today.”

The relationship between hydrogen & oxygen reliably make water over and over again. They’ve been doing it for millions of years. Essentially the cause and effect can be predicted because it has a pattern that has replicated itself trillions of times over.

Causal Determinism is a finite pattern. And that’s why we can make sense of it.

Imagine now, if another day, the 2 hydrogen atoms and 1 oxygen atom came together and created Carbon Dioxide. And then another day they came together and created Sulfuric Acid. And then another day they came together and created Calcium Carbonate… that would be confusing.

Their causal relationship would cease to make sense.

And in fact, we might better describe that if water, carbon dioxide, sulfuric acid, and calcium carbonate were all created, there would, in fact, be four different causes for four different effects.

A cause and effect relationship is deterministic. So a singular cause doesn’t have multiple contradictory effects.

Nor does it change day by day.

The 2 hydrogen atoms and 1 oxygen atom don’t behave differently on a whim.

But living things don’t exist as causal patterns. Every second of time has a kind of freedom and spontaneity for those who are alive to experience it.

And furthermore there are trillions of animals alive right now. And trillions and trillions of animals who have been alive since the beginning of time.

That’s an incredibly unnecessary and complicated deterministic universe with an infinite amount of movements.

Here’s my problem with deterministic free will:

Each and every day we make thousands of micro decisions. They are not the same each and every moment. Nor are they the same every day.

But if, as determinism posits, any single behavior we possess is deterministically caused, then a different deterministic force would have to exist for every single deterministic effect.

In the universe, a single causal relationship doesn’t have moods that enable it to choose a different effect day by day.

Hydrogen doesn’t choose to turn oxygen into water because of its mood. Oxygen doesn’t choose to turn hydrogen into water either. And they can’t choose a different effect tomorrow.

The atoms come together and the effects are pre-determined and inextricably linked.

So if our willpower is deterministic, then every single new movement we make would have to be inextricably linked to a different cause.

Now, if every day we ate 100 grams of white rice with our right hand at intervals of 20 seconds per bite, with 15 chews per spoonful, while sitting in the same chair, sitting on the left side of the table, at precisely 6PM and finishing eating those 100 grams 10 minutes later… then I can see how we could conclude that our will is deterministic and there are causal forces creating the actions we take.

Because the actions that we take are finite and predictable.

Although, in this example, they might be better described as mechanistic.

But my point is that the periodic elements behave like this. They reasonably do the same thing every time. Unless a different cause interferes.

They don’t choose a different result each day. And certaintly not infinitely.

So if we eat a different food each day. If we eat at different times each day. If we chew at different rates. If we stop to speak between some bites but not others… then we must have a NEW cause for each and every micro decision made.

Occam’s Razor

Multiply that by the amount of moments we’re alive. And multiply that by the amount of humans and animals that live in this world… I mean, imagine if every single living animal that can move itself had a different causal force for each and every movement they make.

Unlike H2O, which is reliably created trillions of times over, this universe would be absolutely inundated with random-ass forces that only work once. A single cause creates only one effect today and then ceases to exist. Poof. Gone. Up in smoke. And tomorrow you need 10,000 new causes for every random new action you take.

This is where Occam’s razor comes in.

Occam’s Razor: a scientific and philosophical rule that entities should not be multiplied unnecessarily. And the simplest of competing theories should be preferred to the more complex.

The idea of deterministic will existing in a causal relationship seems insanely tedious and cumbersome.

And let’s face it––also pointless.

What’s the point of being alive to exist as the mechanistic effect of a pre-determined cause?

When, on top of which, we’re not even a finite effect. No, we have millions of different causes that create variable effects that convince us that we’re freely moving (but we’re not).

And then this deterministic cause gives us other feelings: like deliberation, anxiety, doubt, disappointment, regret, anger – all kinds of reactions that are completely unnecessary if we never had a choice.

In H2O, there’s no deliberation, in which hydrogen doubts it can become water.

It doesn’t feel anxiety about whether marrying oxygen and becoming water is the right choice.

It doesn’t fear that it will try to become water and fail to do so.

It doesn’t feel remorse that it became water, and down the road realizes it wanted to become something else.

If each and every movement we made was not a movement we made––but was a force moving us… then where the hell does the neurotic sentience fit in?

We don’t even choose to feel neurotic. A cause made us choose an action and then another cause made us feel neurotic over the action we had no control over.

I mean, it’s an exercise in the most fruitless deterministic design ever imagined.

I’m not a mathemetician. I’m not a phycisist. I’m not a chemist. I’m not even a statistician.

But I am a philosopher, specifically philosophy of mind.

And I can describe to you - as a philosopher - how I conceive of the idea of willpower in similar language as quantum mechanics.

With randomness and probability.

And I can promise you that it is a SIMPLER explanation than the uncessarily cumbersome explanation of determinism.

Because I do believe that the simplest answers are the most reasonable.

Free will makes sense from the inside. To exist in it, can help you understand it.

And I don’t think that you necessarily need to go to the atomic level to study the behavior of an electron in order to understand free will.

But you do need to define what it means to be alive first.

This concludes:

Part 1: Quantum Mechanics, Material Determinism, & Occam’s Razor

Join me for:

Part 2: Being Alive, Sentient Movement, Religious Determinism, & Entropy

Part 3: Intelligence & Willpower Via Causal Relationships

Questions For Discussion

Is the free will determinism theory defined by Newtonian Physics?

How can free will possibly be more deterministic than an electron’s uncertain behaviors, as mathematically mapped out by Paul Dirac in Quantum Mechanics?

Is determinism too cumbersome to pass the Occam’s Razor test?

How To Discuss

You can comment below OR subscribe to the Substack to find the chatroom and continue discussing this and other topics with us there.

All free subscribers are able to comment and join our weekly discussions. Paid subscriptions are only voluntary donations and are not required to participate!

Bluesky

You can also find a shorter version of this discussion on my profile on BLUESKY. Each Sunday question will be posted and discussed in shorter form there, as well.

Subscribe to The Beat Philosopher for more discussions like this every Sunday.

All Rights Reserved © 2025 Elephant Grass Press, LLC

You can always unsubscribe in a single click. Thanks again! And please tell a few friends if you’re enjoying your subscription!

1&2) Hydroden and Oxygen don't reliably react to create water. They reach a kind of balance of forwards and backwards reactions with a ratio in line with the probability.

Every chemical equation is really a ratio

2h2 + 02 => 2 H20

I'm failing to look up the actual ratio because the internet insists on telling me the ration of hydrogen to oxygen instead, but natural water is maybe 99.99996% h20, and 0.00002% Oxygen and 0.00002% Hydrogen, and that's stable. Water is decomposing into Hydrogen and Oxygen at the same rate as Hydrogen and Oxygen are reacting to form water. Furthermore, the exact ratios are changing from moment to moment - maybe this second, it's 0.0000199996% Hydrogen, and next moment it's 0.00002000007% Hydrogen.

Determinism emerges from many probabalistic molecule reactions, but the results match the probabilities very much more closely than the randomness with which the individual molecules react. Hydrogen and Oxygen very much make water, at least if it is hot enough.

For that matter, at a much lower ration, Hydrogen and Oxygen really do make Carbon dioxide, as multiple hydrogen atoms fuse to make carbon. That ratio is probably so small it's never happened on earth (kind of a guess, I'm not doing that much maths for a forum post, I don't even know if I could), but the probability of a carbon dioxide atom being emitted by Hydrogen and Oxygen is not zero.

This is an example of at least two things:

1) An understanding being "good enough". It's useful, it may not be the whole story, but it does tell you roughly what will happen. The whole story is usually much wider and more interesting, and sometimes feels unreasonable.

2) Lots of probability events "summing up" to something very deterministic. If you run 1,000,000 fair coin tosses, the result will be very close to 50% of them are heads. But it's unlikely to be exactly 50%, it's more likely to be off by a few. The wider story does have some bearing on the truth.

3) Does deterministic free will meet the test of simplicity?

Free will as an idea has concrete ideas associated with it.

Was it my fault that I crashed my car? Could I have chosen otherwise? Perhaps it was just inexperience?

Do I reach my decisions myself? Perhaps the media environment plays a significant role? I tend to think we're usually trying to please someone with our actions, often not ourselves as such, but to get an advantage in a relationship. We aren't selfish but we are, very selfish. We want to please someone else because that benefits us. Which might explain our discussions about free will - we're constantly doing everything for someone else, no wonder we don't feel free.

While I know what you’re trying to get at with the water analogy, I feel like it’s a faulty analogy.

The reason two hydrogens and one oxygen don’t form sulphuric acid or carbon dioxide, is because there is no sulphur or carbon in the reactants. The element is determined by the number of protons in the nucleus. One element cannot change into another element unless it is undergoing nuclear decay or nuclear fusion.

The scenario of two hydrogens and one oxygen forming carbon dioxide would break the laws of physics.

Saying atoms are deterministic because they can’t randomly become another element, is like saying free will is deterministic because we can’t jump to Jupiter.

It is undeniable that we are ultimately limited by the laws of nature. I could decide tomorrow that I’ll be the world’s first trillionaire, but we all know that’s not going to happen.

The universe appears to be both deterministic and non-deterministic at the same time. It depends on what you’re measuring.